L’intelligence artificielle est partout, y compris dans le domaine musical. Qu’il s’agisse de “générer” des musiques à partir de données existantes, de créer une musique 100 % originale ou de réaliser certaines tâches pratiques, les usages sont nombreux et les inquiétudes aussi.

Tag: collage-project

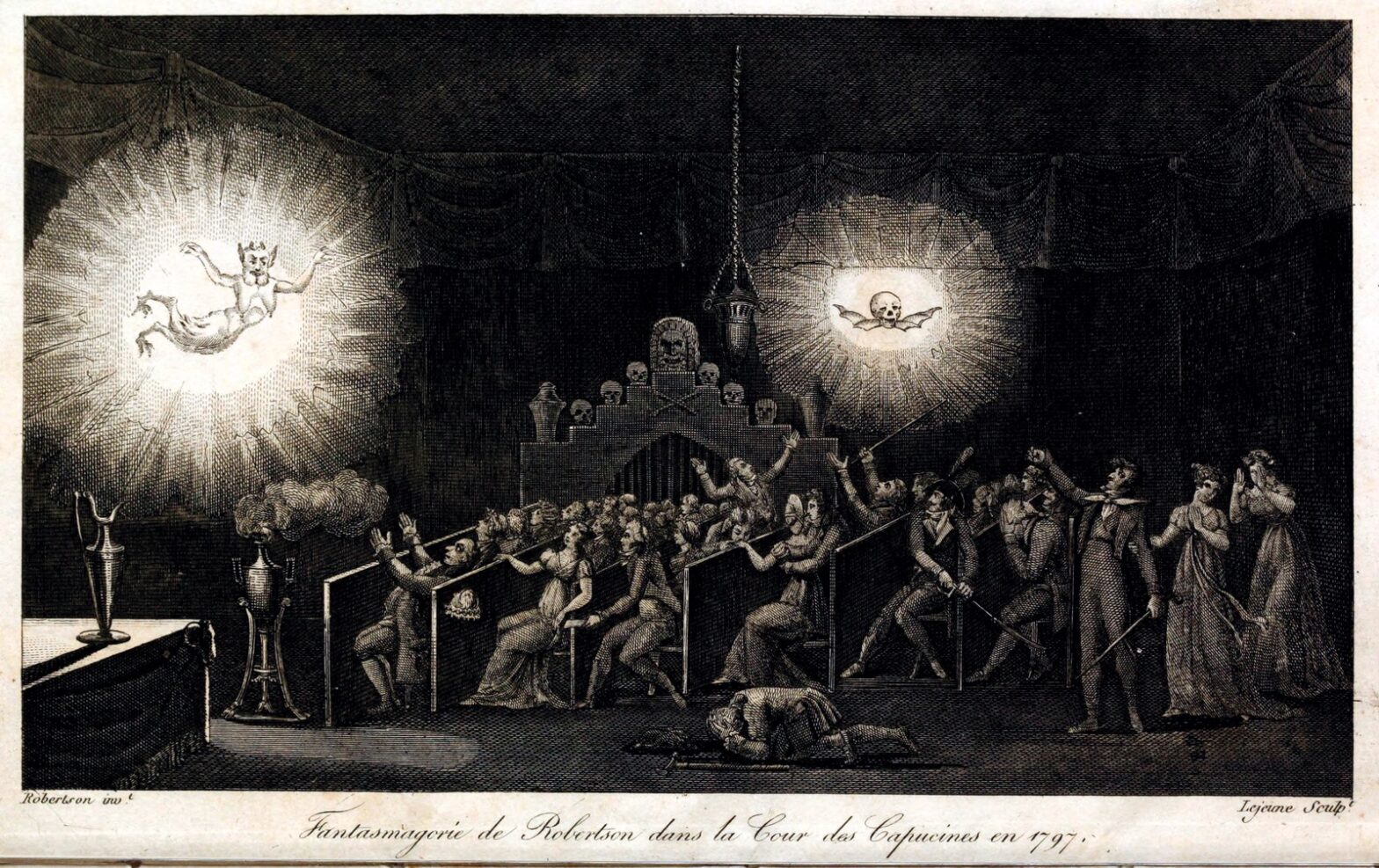

Phantasmagoria @ Academy of Fine Arts of Munich

Phantasmagoria: Sound Synthesis After the Turing Test @ S4

Sound synthesis with computers is often described as a Turing test or “imitation game”. In this context, a passing test is regarded by some as evidence of machine intelligence and by others as damage to human musicianship. Yet, both sides agree to judge synthesizers on a perceptual scale from fake to real. My article rejects this premise and borrows from philosopher Clément Rosset’s “L’Objet singulier” (1979) and “Fantasmagories” (2006) to affirm (1) the reality of all music, (2) the infidelity of all audio data, and (3) the impossibility of strictly repeating sensations. Compared to analog tape manipulation, deep generative models are neither more nor less unfaithful. In both cases, what is at stake is not to deny reality via illusion but to cultivate imagination as “function of the unreal” (Bachelard); i.e., a precise aesthetic grip on reality. Meanwhile, i insist that digital music machines are real objects within real human societies: their performance on imitation games should not exonerate us from studying their social and ecological impacts.